When people ask me what my favourite book is, I think they expect me to say Game of Thrones. Those who know me well, know to their peril, that George.R.R.Martin’s classic medieval inspired fantasy series has caught my imagination, and if asked about it, I fall into the inevitable trap of spending hours talking about plot twists and predictions for the finale that half the world is waiting for and second guessing to. I will, for sake of your sanity, spare you my G.O.T ramblings here.

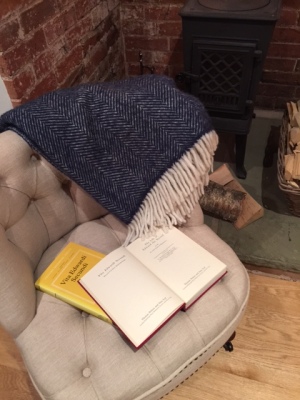

Much to peoples’ surprise, my answer apparently is far more unpredictable. ‘Oh that’s easy’ I say, immediately smiling like I’ve just curled up in the armchair under a woolly blanket next to the log burner on a cold rainy winter’s afternoon with said book (and an occasional glass of wine); ‘it’s the Vita Edwardi Secundi.'(1) As you can imagine, this is not your average read, but when I was seventeen I first discovered this book lurking on a forgotten shelf in a second-hand bookshop on the Charing Cross Road in London. Riffling through its dusty brittle old pages came that evocative sense and distinctive smell of the past. You know the feeling; that special moment when standing on your own surrounded by a room of floor to ceiling shelves crammed precariously with books, you hold your discovery in your hands and gingerly open it for the first time in great anticipation of what you might discover, what adventure awaits and who you might meet on your literary journey. For me, this is particularly magical if the book relates to Edward II. Eighteen years later, I’ve never really put it down. In fact I think I’ve read it so many times, I could possibly quote the whole thing verbatim.

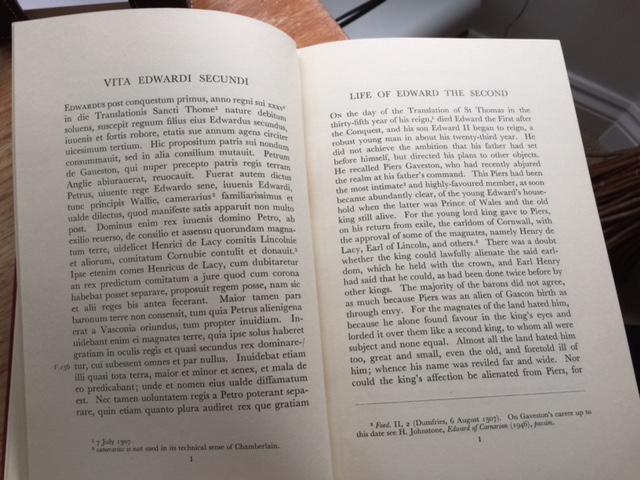

In 1957, N. Denholm-Young who taught medieval history at the University of Wales amongst many other roles of note, took on the task of editing and translating a medieval ‘chronicle’ written, by what the title of the manuscript implied, was a monk at Malmesbury Abbey during the middle or latter part of the reign of Edward II. The subject of the work was of course the king himself; Vita Edwardi Secundi means ‘Life of Edward II’ and covers the events of the reign from 1307 up until a year before his fall from power, when in 1325 the work abruptly ends. The manuscript Denholm-Young was transcribing was sadly not the fourteenth century original, but instead a copy made by the antiquary Thomas Hearne, who made his transcription from the original manuscript in 1729, borrowed from his friend, James West. Fortunately for me, fate was with us that day nearly three hundred years ago, for eight years after Hearne set to his task, the original manuscript was lost, when West’s library in the Temple, London caught fire and many a literary and historical treasure was lost to the nation. Hearne’s version is now kept in safe store at the Bodleian Library, Oxford where Denholm-Young was for a time Keeper of Western Manuscripts. He used in the main, Hearne’s version to translate the manuscript into modern English and his book, the very same copy I hold so dear, contains both the Latin text and an English translation.

So what is all the fuss about? Well, in short the author, most likely a lawyer and not a monk, John Walwayn, had been in royal service of a kind throughout the reign of Edward II and was present and saw many of the events of the king’s time unfold around him at court. He was most likely in the direct employ of the earl of Hereford, who was Edward’s brother-in-law. This gave him access to information, events and people that other writers of the period simply did not always have. Furthermore, the likely date that the work was written, between Walwayn’s retirement in 1324 and his possible death in 1326, is evident in his work in how he writes. In short, we cannot ask for a better eye witness or contemporary to record the history of the time, even though it was written at the end of his life with the benefit of hindsight. The voice is of the time and this for me creates a special window into the past.(2)

That is not to say his record is always accurate or exemplary, but it is rather exciting. What I love about the work is that it feels like a book rather than a chronicle which these types of sources can sometimes be too dry or predictable even if very useful. It does not have the formal style of a year by year blow of what happened per se in the fashion of the traditional chronicle, but reads much more informally like a story – a chronological narrative yes, but one that flows well and less rigidly. Some years the author choses to focus on the details for longer, penning far more pages than in other years, which rather tantalisingly shows us what he was interested in recording.

Walwayn also tried really hard throughout his work to remain as neutral as possible unlike many chroniclers of the day who were installed at religious institutions and only to apt at pouring scorn on the king and his court. Walwayn tried really as much as he could to keep his guard up especially when dealing with Edward, but on occasion shows here and there favouritism against the king in support of the nobles, including the king’s cousin and rival Thomas of Lancaster. The fact that Walwayn was in the employ to the earl of Hereford is not surprising when it comes to his view of court politics. I love this human element which shines through as much today as it did when written seven hundred years ago. When reciting the events of Lancaster’s execution in March 1322, the Vita records, ‘O calamity! To see men lately dressed in purple and fine linen now attired in rags, bound and imprisoned in chains!’(3) On reflecting on events in 1313, following the murder of Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall the year before, Walwayn lets his guard down more than ever and clearly reflects his real view of Edward at this time;

‘For our king Edward has now reigned six full years and has still now achieved nothing praiseworthy or memorable…if our lord king Edward had borne himself as well at the outset of his reign [compared to Richard I], and not accepted the counsels of wicked men not one of his predecessors, would have been more notable than he’.(4) Ouch!

The Vita is also a great source of information for the personalities at play such as Piers Gaveston, leading earls including Thomas of Lancaster and key events, even if his bias shows. He is clearly not a supporter of royal favourites and takes the occasional swipe. ‘Piers remained a man of big ideas, haughty and puffed-up.’(5) Another great asset of the work is that Walwayn takes time to give detailed accounts of the Scottish campaigns and various raids made by Robert Bruce, including the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 as well as the Marcher lords’ rebellion in 1320-21 and the king’s subsequent response.

In amongst the drama of the account, you also get a feel of something about the man beyond the history and the subject of his work he set out to record. In 1320, most of the account of that year is given over to young men being raised high at the expense of their elders. Walwayn about this time had his eye on the bishopric of Lincoln following the death of incumbent John Dalderby, but was not successful in being elected to its seat. His disappointment is, without explicitly saying it, vented out in his work. He just can’t help himself. It seems that even seven hundred years ago, the young and their elders do not always see eye to eye.

The most poignant part of the Vita for me is its abrupt end. It finishes when Walwayn quotes a letter sent by Edward II to his wife Isabella in Paris on 1 December 1325, at a time when the political stakes of Edward’s reign are moving in a calamitous direction. The last sentence of the book reads, ‘But not withstanding this letter mother and son refused to return to England.’(6) What follows next off the pages changes the course of history. It leaves as many tantalising questions about what happened next to the author as to what were the events as seen at court during this turbulent time. Did Walwayn die before his next entry? Or was he in some way caught up, despite his retirement, in the political chaos that swept through the country the following year meaning he was unable to complete his work? We will never know and that is something that makes me smile and ponder every time I read it. It’s an unintentional cliff hanger that is never leading to a sequel.

If you ever want to peer through a window into the distant past and fancy a good weekend read, grab yourself a copy, either from a second-hand bookshop or on Amazon. Wendy Childs, historian at the University of Leeds, went back to Hearne’s manuscript and made her own translation in 2005 and this work is printed by Clarendon Press.(6) For me, whilst Childs’ transcript is excellent, there is nothing better than returning to a book that feels a bit like a first love, which Denholm-Young’s version is. Unforgettable and always brings a smile to my face. Happy reading.

Notes

(1) N. Denholm-Young. Vita Edwardi Secundi Monachi Cuiusdam Malmesberiensis: The Life of Edward the Second by the So-called Monk of Malmesbury. ed & trans by (Nelson Medieval Texts, 1957). – quotes used throughout the body of this work are taken from this text and noted as ‘Vita’.

(2) Further Reading. ‘The Authorship of the Vita Edwardi Secundi’. in Collected Papers: Cultural, Textual and Biographical Essays on Medieval topics. N Denholm-Young. (University of Wales Press, 1969)

(3) Vita, 124-125

(4) Vita, 39-40

(5) Vita, 16

(6) Vita, 145

(7) Childs, Wendy. Vita Edwardi Secundi: The Life of Edward the Second (Clarendon Press, 2005)

What a great joy that sounds like. There are all kinds of reasons why the story might not have continued. He might just have died, he might have died as a result of the civil war, he might have been told in no uncertain terms to stop writing, he might not have been able to bear telling the tale of Isabella and Mortimer and how they turned out to be worse than Edward II, or Hearne might not have copied the whole manuscript before he returned it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like your thinking. I had wondered to, whether Hearne gave up transcribing, but I could not think why he would send it back to West unfinished when he had marked down so much of the reign. The last year was so dramatic. Feels like Hearne did his job, which in my mind leaves the tantalising possibilities that you outline above. S

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps Hearne didn’t give it back, perhaps West demanded it back, or there was a time limit on the loan, or one or the other of them was going somewhere else and it had to be returned. I could do this all day, but won’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person