Having spent the last week with a very painful wisdom tooth infection that passed into my jaw, I could only just about survive the insufferable pain because of modern day antibiotics and hardcore pain killers. For anyone out there who suffers from this malady, will know all too well that toothache or an infection in the mouth is positively mind numbing. Your whole world suddenly stops as you battle the overwhelming and utterly debilitating pain. As I lay there, the infection beginning to ebb, it got me thinking. How on earth would I have coped had I been alive seven hundred years ago, and was toothache a widespread problem?

It most certainly was judging by the amount of manuscripts written and architectural bosses found in churches and other medieval public buildings of tortured souls with toothache.

The most famous of all medieval kings to suffer agonising tooth infections in the very late medieval period was Edward V, who before his death in the Tower of London in 1483 (perpetrator not mentioned here because that’s a whole other debate), suffered from such chronic attacks that he was put to bed, sometimes for months on end. His jaw was heavily corrupted and his last known bout of infection was shortly after his uncle Richard III had the boy king and his brother, Richard, duke of York ensconced in the Tower of London. Toothache, tooth infections and mouth problems were a common malady in the medieval world and one that universally straddled the social hierarchy. We are fortune today that there still survives a number of manuscripts written by the curious and practising apothecaries who sought to advise and administer treatment a long time past.

In the 1180’s, whilst Henry II reigned in England, Roger Frugard put quill to parchment in Parma in Northern Italy, penning his Chirurgia.(1) For toothache, Frugard determined that you could take a small heated iron or pin and insert it into the skin behind the ear. Afterwards you would take leek seeds and henbane, heat them over a fire and inhale the smoke through a funnel. This he felt would cure the pain. I always have an intense pain in my ear during bouts of toothache and so sticking a pin here is intuitive.

If the gums were black and hard, a sure sign of cancer, Frugard encouraged the reader to cut out the bad tissue, cauterising the wound and using egg yolk to seal it. To keep away further infection the gums were then to be washed in wine and after three days had past post treatment, they were also to be rubbed with alum. Following this a lotion of wine and honey infused with honeysuckle, pomegranate and ginger was to be liberally applied. Many of these ingredients such as pomegranate were luxury items and only afforded to the wealthiest in society.

In an account written fifty years later in Wales, the common treatments advocated for widespread toothache, and more accessible across all levels of society, were herbal remedies. They were varied, but many of the items were readily available such as honeysuckle, ivy bark and leaves of the holly bush. Most of these were either chewed or rolled up into balls and placed between the cheek and the infected tooth;

‘…as long as you walk a mile with moderate steps, and as the saliva collects spit it away. When you think that the ball has been there as long as that, put in another and walk backwards and forwards for the same space of time; after that put in the third, then lie in bed, and warm yourself well, and when you have slept you will be free from pain. This I have proved and have found to be a present remedy for toothache‘. (2)

If Ivy bark and beeswax was not to your fancy, just like swilling out my mouth with warm salt water today is not mine, the medieval inflicted could use a poultice made up of rose water (so long as the roses were red), softened beeswax and butter and applied with a linen cloth. Failing that prayer was the answer. In the fourteenth century praying to St Apollonia, who was murdered by having her teeth extracted by the Romans and then burnt alive in the third century AD, would cure the ache but only if the prayers were said on her feast day, 9th February,

In addition to prayer, bearing in mind that the medieval world was far more superstitious than the culture is today, one could also carry out acts to ward off pain through various rituals.

‘Get an iron nail and engrave the following words theron, + agla + Sabaoth + athanatos + and insert the nail under the affected tooth. Then drive it into an oak tree, and whilst it remains there the toothache will not return. But you should carve on the tree with the nail the name of the man affected with toothache, repeating the following: By the power of the Father and these consecrated words, as thou enterest into this wood, so let the pain and disease depart from the tooth of the sufferer. Even so be it. Amen‘(3)

One can only shudder at the thought of driving a nail under the tooth in the first instance but of course many people must have done so.

Move on a few decades and another medieval text known as The Compendium penned by an Englishman, Gilbertus Anglicus, was widely read and practiced throughout Europe.(4) Rotten teeth and either a very rich or very poor diet can then, as much as now, produce halitosis. Gilbertus called this ‘stinking of the mouth’ and believed the cause was not just the first two above, but could also be related to stomach problems or lung disorders. Like Roger Frugard in the twelfth century, Gilbertus in the thirteenth recommended that any rotten flesh in the mouth be immediately cut out and cauterised. (Remember no anaesthetic then, just lots of strong wine or ale to help numb the pain amongst other herbs). The sanitising effect of alcohol has for thousands of years been well known.

To ease bad breath he also recommended a form of mouthwash made up of wine, mint and birch, so not much different from today given that some mouthwashes still contain ethanol (alcohol) and many are mint flavoured. The teeth could also be cleaned daily by rubbing a corse linen cloth along the teeth and gums until they bled, or better still they could be rubbed after every meal, which it seems was the widely adopted approach to cleaning teeth in medieval Europe. The long held belief that teeth were simply not cared for in this period does not reflect the surviving evidence, albeit many teeth nevertheless ended up rotten, blackened and corrupted. Gilbertus noted that if the teeth were so far gone they should be rubbed with burnt powdered deer antler to help revive them. Only the king and the nobility and those appointed by them were eligible to hunt and kill deer, so again this remedy was not for the masses unless they turned to poaching and risked the hangman’s noose.

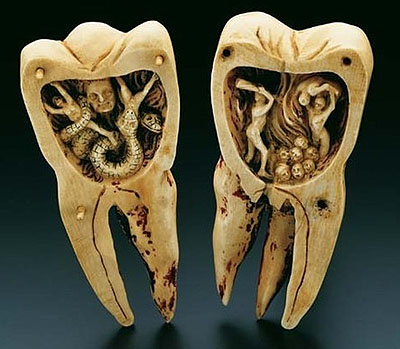

One of the more common occurrences were worms in the teeth, something that thankfully is not seen much across the modern globe. Small parasitic worms, acting much like intestinal worms, burrowed in the teeth and could not only cause immense pain but could be felt wriggling by the individual. Whilst one imagines they must have been a good source of protein, the thought of tooth worms I am sure makes us more than a little queasy today an probably then to. Treatment for this in the main had not changed since Pliny was writing at the height of the Roman Empire and meant the affected should inhale the smoke from burning henbane. There are sources to suggest that in Wales and therefore possibly more widely in England, nightshade was also used. The physicians of Mayddfai recommended;

‘Take a candle of sheep’ suet, some sea holly seed being mixed therewith, and burn it as near the tooth as possible, some cold water being held under the candle. The worms will drop into the water, in order to escape from the heat of the candle’.(8)

The pain of the heat from the candle alone is enough to make one shudder let alone the risk of burning the face.

Finally, if a tooth caused so much pain that it had to be removed, there were many options to help bring about extraction. Other than physically forcing it out, the Physicians of Myddfai in Wales in the thirteenth century suggested;

‘Take some newts, by some called lizards, and those nasty beetles which are found in fens during summer time, calcine them in an iron pot and make a powder therof. Wet the forefinger of the right hand, insert it in the powder, and apply it to the tooth frequently, refraining from spitting it off, when the tooth will fall away without pain. It is proven‘(5).

or

‘Seek some ants with their eggs and powder, have this powder blown into the tooth through a quill, and be careful that it does not touch another tooth‘. (6)

Whilst one of Edward II’s physicians, John of Gadsden who wrote the Rosa Anglica sometime around 1314 when the king was off to Bannockburn to fight the Scots, Gadsden suggested that the process of extraction could be achieved by smothering the tooth with the fat from a dead green tree frog or cow dung or partridge brain.(7) If you wanted the teeth to grow back then you had to apply the brain of a hare to the gums. Either modern medicine is missing a trick here, or Gadsden was perhaps being somewhat creative. Let’s hope Edward II never needed a tooth extraction!

So, seven hundred years later as I bemoan my painful jaw, I can at least rest in the knowledge that our modern medicinal practices are easier to apply and be thankful beyond measure that I do not have dreaded tooth worm!

So as you brush your teeth this evening and look into the mirror, remember what our ancestors endured to keep their pearly-whites, well… pearly white.

Keep them clean and minty fresh folks!

Notes

Principal Source and extracts used widely here: The British Dental Journal 197, 419 – 425 (2004)

(1) The British Dental Journal citing Hunt T. Anglo-Norman Medicine I. Roger Frugard’s Chirurgia and The Practica Brevis of Platearius. pp5, 6, 19, 20, 57–59. Cambridge: D S Brewer, 1994.

(2,3,5,6,8) The British Dental Journal citing Pughe J. The Physicians of Myddfai. pp xix, 46, 49, 51, 53, 55–57, 302, 309, 310, 317, 335, 344, 352, 354, 367, 368, 374, 375, 392, 393, 453, 454. Felinfach: Llanerch, 1993.

(4) The British Dental Journal citing Getz FM. (ed) Healing and Society in Medieval England A Middle English Translation of the Pharmaceutical Writings of Gilbertus Anglicus. pp lv–ivii, 89–97. 89–97. Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1991.

(7) The British Dental Journal citing Talbot CH, Hammond EA. The Medical Practitioners in Medieval England A Biographical Register. pp 148, 149 London: Wellcome Historical Medical Library, 196 and Cholmeley HP. John of Gaddedsen and the Rosa Medicinae. pp, 49, 56, 57. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912.

Facebook: Fourteenthcenturyfiend

Reading this made my teeth hurt. I’d never heard of teeth worms before and I don’t really want to hear about them again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me to April. It’s amazing (and a little disturbing) what you can uncover when researching.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. Holly and Ivy I thought are poisonous, probably would stay away from those. I like the spell with the oak tree best, must try that next time 👍🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person