Edward II is so often remembered because of his close male favourites. The one that history records with the greatest of infamy is Piers Gaveston. His twelve years spent at the side of the king, beginning when Edward was still heir to the throne and ending with Gaveston’s untimely and dramatic death in 1312, is marked by contemporaries now and then with much opprobrium.

Piers Gaveston’s career was an extraordinary one. Born to parents Arnaud de Gabaston and Claramonde de Marsan, both important members of medieval Gascon noble society in the Duchy of Aquitaine, Piers Gaveston grew up fast whilst demonstrating great martial prowess. His martial efforts, supporting his father who was a sworn man of Edward I, eventually impressed the king enough to consider him a suitable role model to join the prince’s household. Gaveston was two years older than Edward, most likely born around July 1282; Edward, a little younger, was born on 25 April 1284. They had a lot in common. Both their fathers were often absent at war, their mothers died when they were both young; Edward six and Gaveston five. They also shared a love of fine clothes, music and entertainment. During these heady early years, their friendship grew and spilled over to something more intimate. This intimacy would bind the two men together against all odds.

‘Of Edward’s love for Piers it was reported that “upon looking on him the son of the king immediately felt such love for him that he entered into a covenant of constancy, and bound himself to him before all other mortals with a bond of indissoluble love, firmly drawn up and fastened with a knot”.(1)

It is far to easy to apply modern terms of sexual identification onto people’s intimate behaviours in the past. This in itself is made more complicated by the absence of evidence that explicitly states what people did behind their closed doors. Edward II of course married Isabella of France, and whilst initially a political union, was for at least fifteen years, a highly successful marriage. Only the benefit of hindsight which focusses on the last four years of Edward’s reign does this truth become distorted and falsely recorded by those who seek to overplay the facts. They had four children, most notably their eldest son who became Edward III in January 1327 following his father’s fall from power. Edward II also had one illegitimate son called Adam, who was fathered before he ascended the throne and who died in 1322. However, Edward II also had intimate and intense relationships with men, by far the most notable with Piers Gaveston. Whilst they would not have identified themselves as ‘bisexual’ at the time, the word itself a modern evolution, their behaviour was in the modern sense of the word bisexual and helps us today understand their actions using this framework.

It is far to easy to apply modern terms of sexual identification onto people’s intimate behaviours in the past. This in itself is made more complicated by the absence of evidence that explicitly states what people did behind their closed doors. Edward II of course married Isabella of France, and whilst initially a political union, was for at least fifteen years, a highly successful marriage. Only the benefit of hindsight which focusses on the last four years of Edward’s reign does this truth become distorted and falsely recorded by those who seek to overplay the facts. They had four children, most notably their eldest son who became Edward III in January 1327 following his father’s fall from power. Edward II also had one illegitimate son called Adam, who was fathered before he ascended the throne and who died in 1322. However, Edward II also had intimate and intense relationships with men, by far the most notable with Piers Gaveston. Whilst they would not have identified themselves as ‘bisexual’ at the time, the word itself a modern evolution, their behaviour was in the modern sense of the word bisexual and helps us today understand their actions using this framework.

Gaveston married Edward II’s niece, Margaret de Clare, in December 1307 at Berkhampstead castle and they went on to have a daughter together, named Joan who was born in 1312. Most rulers and men amongst the magnate class at this time had a string of illegitimate children born from unions long or short with other women outside of their marriage vows. The fact Edward had marital affairs to was a product and almost expectation of his age. To the modern eye, this degree of promiscuity feels at odds with our modern values, but nevertheless needs to be seen in context of the time. The fact Edward’s extra-martial affairs were with men comes under more scrutiny with writers looking back at his life after his fall from power, seeking to find causes for his failings which were often embellished and their actions set out of context, including his predilections for men.

Same sex relationships were condemned by the church and the penalties could include castration or burning, but for those at the highest level of society, especially the king, they were often set apart and their actions overlooked. Their perceived crime was either not openly acknowledged or overtly commented on for fear of retribution or out of respect. Essentially, for contemporaries, what a king chose to do behind the closed door of the bedchamber was his business, even though the chamber itself was never that private, attended by household staff. So Gaveston’s relationship with Edward was not in itself the reason for the hostility that built up around Piers within the first six months following the king’s accession in July 1307.

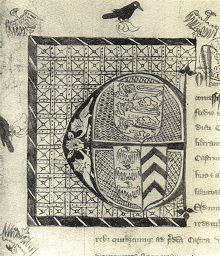

The principal reason, but by no means exclusive, was Gaveston’s elevated position and control over royal patronage. As Edward rose in power when he became king, so was his intention to elevate Gaveston to the highest ranks of the nobility. In August 1307 the king granted to Piers the earldom of Cornwall which the magnates of the time supported and attached their seals to the charter of enfeoffment. Only the earl of Warwick’s seal is absent. Edward wanted to give his lover a status that befitted his closeness to the king. Gaveston’s lucrative marriage to the earl of Gloucester’s sister Margaret in quick succession did not help matters. Their intimate relationship meant Edward and Gaveston spent a great deal of time in each others company, especially at the start of the reign, and by virtue of his office, access to a king was widely sort after and a jealousy guarded affair, highly regulated and full of precedent which was underpinned by the strict hierarchical society of medieval England. However, with continued land grants and gifts for his retinue and associates, Gaveston had secured unwitting access by virtue of his intimate relationship with Edward to royal patronage that other magnates of the day could not hope to aspire. In an age when land and titles meant power, Gaveston’s access to Edward upset the apple cart. There are many more reasons, that layered together create a unified hostility to Gaveston, but the access to patronage was by and far the greatest reason for opposition to him.

That opposition became life threatening. From 1307 to 1312, in a bid to separate the king from Gaveston so the nobility could gain access to Edward and restore what they felt where their traditional sources of power and patronage, pressure was applied on the king at critical times during Edward’s early reign. Gaveston suffered three exiles from England, the first enacted by Edward I months before the king’s death, the latter a result of clause 20 of the Ordinances, legislation imposed on Edward II which demanded a final solution to what the magnates believed was an ‘evil councillor’ and their principal adversary to the king’s affection. His removal they felt would enact the chance for ‘good government’. The Ordinances made it clear; Gaveston was to leave England and all the domains of the king, never to return or, if he did, to face the full penalty of the law.

Piers Gaveston, under Edward’s direction, returned in January 1312, two months after he was forced to leave for Flanders. Determined to bring him down, the earls of England led by Thomas of Lancaster, the king’s cousin, set off around the country to capture him. Besieged at Scarborough castle and without much hope of holding out, Gaveston surrendered to the earl of Pembroke under generous terms possibly engineered by the king, who was hunkered down at York. Agreeing to take Gaveston south to his castle at Wallingford under safe protection until the next parliament, Pembroke believed his oath to protect the earl of Cornwall was sufficient to keep him safe. It wasn’t.

During the night at Deddington in Oxfordshire whilst Pembroke was off visiting his wife, the earl of Warwick who had long since hated Piers Gaveston, surrounded the house he was being held in under guard and seized him, marching him back to Warwick Castle. There after a mock trial attended by the earls of Lancaster, Hereford, Warwick and John Botetourt, in which Gaveston was not allowed to speak to defend himself, he was summarily sentenced to death. The next day, 19 June 1312, just after dawn, the twenty-nine year old Gaveston was taken from his cell and forced a few miles north of Warwick to Blacklow Hill which belonged to the earl of Lancaster, and there as the earls watched on, was handed over to two Welshmen. One ran him through with a sword, whilst eventually the second hacked of Piers’ head.

The death of Piers Gaveston was nothing short of brutal murder. When Gaveston returned from Flanders, Edward II had openly revoked the Ordinances, the legal framework which prohibited Gaveston’s return. It also meant he was taken back under the king’s royal protection. In short, the trial held at Warwick and the sentence passed against him had no sound legal basis. The action of his mock jury at Warwick castle was simply mob rule underpinned by savage brutality.

The murder of Piers Gaveston had a profound impact on England and Edward II in particular. Edward would spend ten years seeking revenge on those who murdered his lover. The king’s response, long in the waiting, was to be as brutal as Gaveston’s murder itself when he had his cousin’s head hacked off outside the walls of Pontefract castle in March 1322. The intervening ten years created enormous political instability in England as trust between the king and the Blacklow earls was highly strained, most evident in his intensely difficult relationship with Lancaster.

There is much to write about Piers Gaveston in future posts, but I hope this very high level, whistle stop tour over a fraction of Gaveston’s life has been something of interest. There is certainly more to follow, along with key people in Edward’s reign, including Thomas of Lancaster, Queen Isabella, the earls of Warwick, Pembroke and Hereford and many more.

Notes

(1) Hamilton, Jeffery. Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall 1307-1312. citing Haskins, G.L. ‘A Chronicle of the Civil Wars of Edward II’, (Speculum, 1939)

Images

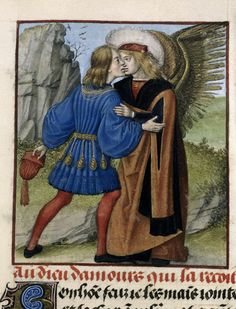

Two Men: ‘Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, Roman de la Rose’. The two men in this image are exchanging the kiss of fealty and is not intended by the illuminator as a representation of same-sex interaction.

Piers Gaveston’s Coat of Arms – Charter of Enfeoffment. National Archives.

Gaveston’s Cross at Blacklow Hill, nr Warwick. (Author’s collection)

Facebook: Fourteenthcenturyfiend

Twitter: @SpinksStephen

Great reading and information thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person