Until 1321 Isabella’s marriage to Edward II had proved successful. They had been married for thirteen years, produced four children and worked in a mutual partnership which appeared affectionate and productive. Isabella’s powers of queenly intercession were used in a conventional way and she had the support of her husband in influencing policy where she could for the help of others; mainly in regards to women, children and the church. The queen stood by her husband as he doggedly battled with his over mighty cousin, Thomas of Lancaster and in this Isabella excelled.

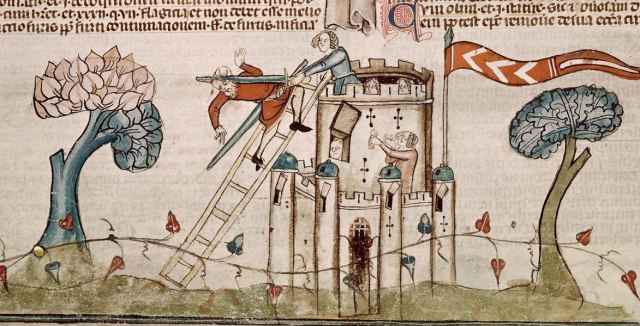

This was no more true than on 3 October 1321 when the queen made an unannounced stop at Leeds castle in Kent on her way allegedly to pilgrimage at Canterbury.(1) It was a ruse. Inside the castle was the wife, children and garrison of her husband’s enemy Bartholomew Badlesmere, until recently a senior loyal servant of the crown now turned rebel. Months previously Badlesmere had deserted the king and joined the rebel Marcher lords as they ravaged and pillaged the manors, lands and estates of Edward’s favourites, the Despensers, who in turn were forced by the rebels into exile, agreed under duress by a reluctant king during the Westminster parliament only two months earlier. The king, who had declared over dinner on 16 August to Hamo Hethe the aged bishop of Rochester that he would ‘make such an amend…that the whole world would hear of it and tremble’, made good on his promise.(2)

Isabella, agreeing with the injustice that had been forced upon her husband, appeared only to happy to help even if that meant compromising her safety. As the queen and her retinue, a mix of ladies of her court and knights of her household approached the gatehouse and sought entry for the night, a suspicious lady Badlesmere refused admission. Isabella insisted, as was the plan, and things turned ugly. Eventually the queen’s patience snapped and attempted to force her way in outraged at this breach of medieval hospitality. The castle garrison let loose their arrows and Isabella was forced to flee with what remained of her retinue, some of them having been injured or worse killed.(3) In response, Edward II had his pretext to move against the rebels, and what happened thereafter brought about one of the highest points in his reign. He overcame his enemies and executed Thomas of Lancaster in March 1322. Isabella’s role had been critical to the whole plan and one the queen played willingly.

However, unwittingly the queen’s participation had a much more devastating impact on her personally than she could have foreseen that day outside Leeds castle. The destruction of the Marcher lords allowed for the continued, and now unchecked, rise in power and status of the Despensers. Hugh Despenser the Younger had been appointed royal chamberlain in 1318 and confirmed in role by the common consent of the magnates in 1319, but now was able to apply his manipulative influence over Edward II which dominated both the king and the court. It’s more than likely that at some time after 1319 Hugh and Edward became lovers although this is not entirely clear. If they did not, Edward was certainly enraptured by him. Hugh, whose reputation for emotional manipulation, violence and insatiable greed, played the political game to his best advantage.(4) Writing to his sheriff John Inge of Glamorgan in 1321, he ordered his man ‘to watch his affairs that he [Despenser] be rich and may attain our ends’.(5) Married in 1306 to Edward II’s niece, Eleanor de Clare, one of the three Gloucester heiresses, Despenser through right of his wife became the wealthiest of the barons in 1317 when they inherited lands in the marches of Wales. Whilst he never secured the title of earl, he nevertheless coveted the former earldom of Gloucester and its vast lands and estates. Hugh, greedy and avaricious began a land grab as soon as he and his wife inherited, and after his return to Edward’s side in 1322, his bullying and acquisitiveness became unstoppable.

Isabella became yet one more target.

The earliest signs that the queen’s relationship with Hugh was strained came in the late summer of 1322. Following Edward’s extraordinary defeat over his enemies at home, the king and his court took the battle to Robert Bruce, who since his victory at Bannockburn was yet to be officially recognised as king, either by Edward, the pope or the rest of Europe. Despite the seize of the English army Edward and his war council were outmanoeuvred. Forced to retreat, the queen who had been safely ensconced at the fortified Tynemouth Priory, suddenly found herself cut off in England behind enemy lines as the Scots advanced south in pursuit of the king. Despite popular tradition Edward did not abandon his wife and made urgent plans to bring the queen to safety.(6) However, events moved quickly and forces sent to relieve the queen were captured in battle, leaving Isabella to make her own escape by sea in hostile waters; the Flemish patrolling the North Sea in support of the Scots. It was later alleged by the queen in 1326 that Despenser had abandoned her there with the intention that she would be captured.(7) Whether true or not, Isabella certainly believed it or used it as a political tool against him. From here on in things got tough for Isabella.

Matters became worse in 1324 when war erupted in Gascony, whose lands and title belonged to the duke of Aquitaine who was the king of England. As Isabella’s brother, Charles IV of France and overlord of Aquitaine moved against Edward, his vassal, things got ugly. Charles confiscated the duchy, which undermined the very marriage alliance in 1303 which had brought Edward and Isabella together. In the tortuous negotiations that followed which included mediation from pope John XXII, Isabella was sent to France as principal diplomat in the hope that she could bring about peace and reconciliation between her husband and her brother. Isabella agreed to go and ‘departed very joyfully’.(8) Negotiations were nevertheless hard but in the round peace was temporarily restored. The condition; Edward II had to go to France to perform his long overdue homage for the return of the duchy. It was a fair and traditional deal, albeit full of pitfalls, but one that ultimately compromised the Despensers. This may have been an advantage that Isabella hoped to achieve as a result of this condition, but is not in itself why the condition of homage was laid down. Isabella was making the best of a bad situation. If Edward came to France without the Despensers, she could try to reason with him and recover their relationship which had been slipping into troubled waters ever since 1322.

As war initially erupted in Gascony, Edward had hit back against his brother-in-law in the September of 1324 by imprisoning or deporting French aliens in the country.(9) It was a traditional policy that had been used by his father Edward I in 1294, but allegedly under the advice of Despenser and the much hated Walter Stapledon, Treasurer of England and bishop of Exeter, Edward also removed Isabella’s French contingent from her household. This was unprecedented. Furthermore, as news flooded England of a potential invasion by the French, the king took the unusual step of taking the queen’s lands back under his protection, which included her lands in the south-west, especially Cornwall. Edward acted on bad advice as a means of hitting out directly at Charles IV and not Isabella herself.

The queen’s income was also reduced from her accustomed £4,500 per annum as she no longer had her lands to £2,613 6s 8d (3,920 marks), and not the meagre sums that are often bandied around by later historians.(10) Eitherway, Isabella was furious and humiliated by the imposition. It degraded her status. The traditional yarn that her children were also ‘ripped away from her’ is untrue. About this time the children were awarded their own households, which given their age was the long established custom.(11) Isabella herself, as well as Edward to had been granted their own households when similar in age and at no time during or after this date when later events played out, did Isabella ever cite this as a grievance or an issue against either Edward or the Despensers.

There were even rumours of a potential annulment of their marriage in late 1324, where the king had allegedly sent his confessor Thomas Dunheved to the pope at Avignon to gain papal support.(12) Although Dunheved did go to Avignon it was for different reasons and no evidence survives to support the spurious claim that was drawn from idle gossip. For Edward, the repudiation of his marriage at such a time of intense diplomatic negotiations with France over Gascony made no sense and nor would he have gained papal support for it. The outcome would have been the total loss of his French inheritance something Edward had been working fiercely throughout the last eighteen months to prevent.

By the time Isabella reached Paris and negotiated a peace settlement with her brother, the Despensers and key councillors surrounding the king such as Walter Stapledon and Robert Baldock, the chancellor were nothing more than open threats to the queen. Isabella’s traditional role as a wife and queen had been undermined and she was above all angry. Despenser the Younger knew his power only lasted so long as he was in Edward’s company and could guarantee his ear. Given his recent behaviour and advice which had discredited the queen, he was far from welcome at the French court. At the very last minute Despenser convinced Edward that should he go to France and leave them behind, they would be murdered in a fashion similar to Piers Gaveston in 1312.(13) The king, evidently torn, eventually agreed to send his son, the young Edward in his place. Before he set sail, Edward II invested his eldest son and heir with one of his oldest titles, the Count of Ponthieu and also the Dukedom of Aquitaine so he could perform homage for these French possessions in the king’s place.(14) It was a grave miscalculation.

Once in France, the young Edward was received by his mother and his uncle at Vincennes and there performed homage for Ponthieu and Aquitaine on 24 September. What happened next was extraordinary. Disgruntled, angry and hostile Isabella made her stand. Refusing to return home to England as had been ordered by her husband, the queen declared in a dramatic speech at the French court in Paris;

‘I feel that marriage is a joining together of man and woman, maintaining the undivided habit of life, and that someone has come between my husband and myself trying to break this bond; I protest that I will not return until this intruder is removed, but discarding my marriage garment, shall assume the robes of widowhood and mourning until I am avenged of this Pharisee’.(15)

This was to be Isabella’s moment. The reaction from the audience was pure astonishment. Walter Stapledon who had been sent with Isabella to France and complicit in her change of circumstances fled from Paris dressed either as a pilgrim or a merchant, took ship and hot-footed it back to Edward and his court in England.(16) The marital strain in their relationship had now spectacularly become a European scandal, and for Edward II was to be his greatest challenge. For Isabella, her position had become intolerable and although Despenser is not explicitly mentioned, it was all to clear whom the queen targeted her anathema at.

From here on in this was to be a clash of the Titans, where neither party could afford to fail. For Isabella, things were about to get even more complicated. For before the end of the year the queen was seen in the open company of Edward’s most recent and dangerous of enemies, the exiled baron of Wigmore, Roger Mortimer.(17)

What happens next is worthy of a Game of Thrones novel and is the subject of the final instalment of Isabella: Wife, Queen Rebel (Part Three).

Notes

(1) Ann Paul, 298

(2) Parliamentary Texts, 164, 169

(3) Ann paul, 298-99

(4) Anonimalle, 92-3. Murimuth, 33. Le Baker, 11. Brut, 212. Ann Paul, 292 all attest to the manipulative power of Despenser the Younger.

(5) J. Goronwy Edwards, Calendar of Ancient Correspondence, 219-20

(6) Phillips, Edward II, 430-31

(7) Holmes, Judgement on the Despensers, 263-7

(8) Vita, 135

(9) CCR, 1323-7, 204, 206-7, 209-11, 216

(10) Buck, Walter Stapledon, 152. n166

(11) Warner, 185

(12) Lanercost, 249. Ann Paul, 337

(13) Murimuth, 44. Vita, 140

(14) Sardos, 243-5. Ann Paul, 309

(15) Vita, 143

(16) Ibid, 142. Buck, 157

(17) Foedera, 619. CCR, 1323-27, 543

Images

Feature Image & Three: Jean Froissart (Bibliothèque Nationalé de France, Paris). Isabella arrives at the gates of Paris.

Image One: A garrison defend their castle

Image Two: A queen

Image Four: Jean Froissart (Bibliothèque Nationalé de France, Paris). Young Edward (later Edward III) performs homage to Charles IV.

Facebook: fourteenthcenturyfiend

Twitter: @Spinksstephen

I really don’t understand how Edward II became so enamoured of a man like Despenser. He seems to have been little more than a brutish bully. I suspect that view has been influenced by historians and novelists who have sided with Isabella.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There is a part of me that thinks, and contemporary evidence which support the view, that Despenser was simply excellent at emotional manipulation, and by that I mean hardcore emotional manipulation. Today we would call it abuse. I believe he managed to create an emotional hold over Edward which came to dominate him because Edward was physically attracted to him at first. Despite his role as king, Edward was after all just human and at the hands of a skilful manipulator, the latter knew how to keep develop and more importantly sustain that hold. It would have become quite sinister. That’s why I firmly believe the rebellion of 1326 happened. There was no real way of breaking the spell by this point, even after Isabella refused in 1325 to come home.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I can understand that there must have been a sexual attraction, but it does make Edward look weak, in that he wasn’t able to break away from an influence which everyone else knew was malign.

LikeLiked by 1 person