Aymer de Valence is not a name that leaps out of the annals of history. Many would be hard pressed to place him, let alone have a sense of his many achievements. But his achievements were great, and he had an impressive pedigree; his great-grandfather being William Marshall, one of Christendom’s greatest knights. His career spanned the larger part of his cousin’s reign; that being Edward II. He was an astute diplomat, a politician, skilled in military arms and one of few men who appeared to want peace in England, success in Scotland and a restitution to traditional rule where chaos and upheaval was the order of the day in early fourteenth century England. In an age when his contemporaries like the earls of Lancaster and Warwick applied brutality to enact political reform, Pembroke stood apart as a man for peace, compromise and desired prosperity. Whilst he never fully realised his aims, his central involvement in the reign of Edward II is a critical note in a much wider and far more tragic story.

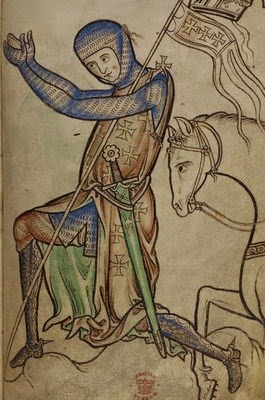

Aymer de Valence had an impressive pedigree. Through his mother, Joan de Munchensy, he was the great-grandson of the infinitely famous William Marshall, one of the greatest knights in Christendom who lived in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, serving many Plantagenet kings including Henry II, Richard I, King John, and perhaps more importantly, the boy king Henry III after his turbulent accession in 1216. Aymer was, through his father, a grandson of Isabella of Angouléme, widower of King John who subsequently married Hugh X, count of La Marche. Aymer’s father William de Valence, was one of the three controversial Lusignan half-brothers of Henry III, who caused much political controversy in England after their arrival there in 1247, during Henry’s reign. They were fierce opponents of Simon de Montfort and William, through right of his wife Joan, became earl of Pembroke. Records are scant, including a description of his appearance, but by the time of Aymer’s birth somewhere between 1270 and 1275, Aymer had inherited by virtue of his nobility, a prestigious name, exceptional connections to the crown and a propensity for martial ability.(1) Yet as the third son, his immediate chances of inheriting land and title were remote, and instead a career had been marked out for the boy in the church. The death of his brothers John in 1277 and William in 1282 whilst fighting in Wales, changed all that, and the stage was then set for a career in the centre of the political stage.

Aymer de Valence had an impressive pedigree. Through his mother, Joan de Munchensy, he was the great-grandson of the infinitely famous William Marshall, one of the greatest knights in Christendom who lived in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, serving many Plantagenet kings including Henry II, Richard I, King John, and perhaps more importantly, the boy king Henry III after his turbulent accession in 1216. Aymer was, through his father, a grandson of Isabella of Angouléme, widower of King John who subsequently married Hugh X, count of La Marche. Aymer’s father William de Valence, was one of the three controversial Lusignan half-brothers of Henry III, who caused much political controversy in England after their arrival there in 1247, during Henry’s reign. They were fierce opponents of Simon de Montfort and William, through right of his wife Joan, became earl of Pembroke. Records are scant, including a description of his appearance, but by the time of Aymer’s birth somewhere between 1270 and 1275, Aymer had inherited by virtue of his nobility, a prestigious name, exceptional connections to the crown and a propensity for martial ability.(1) Yet as the third son, his immediate chances of inheriting land and title were remote, and instead a career had been marked out for the boy in the church. The death of his brothers John in 1277 and William in 1282 whilst fighting in Wales, changed all that, and the stage was then set for a career in the centre of the political stage.

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, the English nobility, comprised of Norman and later Angevin descent, remained closely linked to France and continental Europe. Even after the loss by King John of the greater part of the Angevin Empire in 1204, some English nobles retained estates there, and through his Lusignan family ties, Aymer became heir to substantial French territories which included the four castellanies of Rancon, Bellac, Champagne and Montignac, which he inherited upon his father’s death in 1296. Through right of his grandmother, he even looked set to inherit the vastly more substantial county of La Marche, Angouléme and Fougéres, but this came to nothing when Philip IV applied pressure on the potential heirs to set aside their claims in return for compensation. Under increasing pressure, Aymer relented and gave up his claim in return for an annual pension of 1,000 livres tournois.(2) From 1296 until September 1307 he was known in England as the lord of Montignac, inheriting his English earldom of Pembroke following his mother’s death that September, and was formally granted his estate by the then new king Edward II on 27 October 1307.(3) It is difficult to assess his wealth with exact precision, but his annual worth may well have stood at £3,000-£4,000, making him one of the more affluent of the earls in England at this time. In short, he was a man with clout.

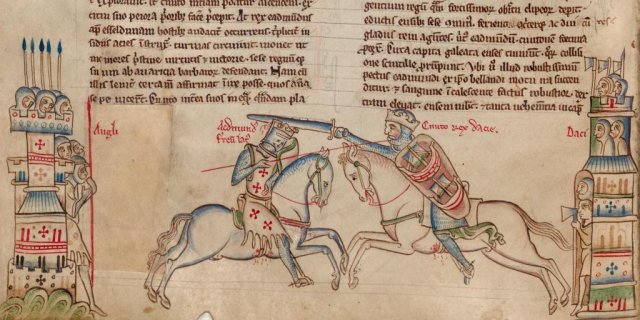

The defining feature of Amyer’s biography is loyalty. He was by instinct a servant of the crown and preferred to proffer his services in that way. During the latter part of the reign of Edward I, Aymer offered his first cousin military service in his campaigns in Flanders in 1297 and in Scotland, being present and fighting first hand in the battle of Falkirk in 1298, in which Edward I and his army defeated William Wallace and other Scottish opponents. Aymer continually proved his capabilities in arms and was also present at the siege of Caerlaverock castle in 1300 (See The Siege of Caerlaverock: A Herald’s Eye Witness Account). He was rewarded for his efforts by a grateful Edward I who bestowed upon him the lucrative barony of Bothwell.(4) He went on to command and win a great battle between the English and the Scots under the command of their recently self-proclaimed king Robert Bruce in 1306 at Methven, but subsequently lost another to Bruce a year later at Loudoun Hill. In all, Pembroke as he became known later that year, was growing in confidence and reputation.

In addition to the campaigns, Aymer also proved himself a capable diplomat, being frequently chosen to take part in royal missions to the continent. In 1299, he was appointed as one of a group of envoys to help agree a French marriage alliance on Edward I’s behalf. This ultimately resulted in the king’s marriage to Marguerite of France, the king’s second wife and half-sister to the king of France. Edward II to relied on Aymer as a negotiator to finalise the outstanding thorny details of his own wedding contract at the end of 1307 and which resulted in the new king’s marriage to Isabella of France in 1308. His connection with the French court, made Aymer a very suitable candidate for frequent diplomatic missions, which he carried out often – almost annually at times – from 1299. He was a trusted courtier, a loyal servant and Edward II’s go-to-man for sensitive, foreign policy. One of Edward II’s strengths was to utilise foreign support in bids to counter or outmanoeuvre his internal opponents, and Pembroke was a major contributor in making that policy happen time and again across the decades.

Aymer himself married twice. His first took place on 18 October 1295 when he wed Beatrice, the daughter of Ralph de Clermont, lord of Nesle in Picardy. His father-in-law was also Constable of France, so again Aymer found himself intricately connected at both the English and French courts. Little records survive allowing glimpses into their married life and therefore Beatrice remains a somewhat elusive character to us today. Their marriage lasted for twenty-five years until Beatrice died in September 1320 after she returned from accompanying Queen Isabella to France earlier that year. Her body was buried in Stratford, beyond the walls of the medieval city of London.(5) But despite their long marriage, there were no living heirs produced as a result. As Pembroke built his power base by increasing his lands, his gains were at risk of loss after his death without male issue. As a result he promptly remarried in July 1321, at a time when England was descending into civil war. His second wife, Marie de Saint-Pol, the daughter of Guy de Châtillon, count of Saint-Pol, was from another well connected French family, but like before this union bore no issue.

From 1307 to 1312, Pembroke’s career and his natural loyalty to the crown were to be severely tested. The political turmoil in the first five years of the reign of Edward II initially began in an expectation for political reforms, long since held back by an irascible and ailing Edward I. Soon those expectations became demands from the nobility and by the spring of 1308, the reform agenda became more complex with the outright, and increasingly more aggressive demands for another exile of Piers Gaveston, favourite of Edward II and who had recently be made earl of Cornwall and had married the king’s niece, Margaret de Clare, sister of the earl of Gloucester (See Piers Gaveston: Life, Love & Death).

As England desecended into charged political chaos, Pembroke found himself desperately wanting to support the king, but was personally opposed to Gaveston’s perceived excesses, his control over patronage and much else besides. Many of the charges against Piers Gaveston do not stick under scrutiny, but what is important to note, is what contemporaries saw, thought they saw or chose to believe. Edward II himself quickly realised that Pembroke often wavered between supporting him and Gaveston and siding with a growing opposition. After Gaveston was exiled a second time in 1308, the king was careful to spend time winning Pembroke back to his side, along with others. In late 1308, he awarded Aymer the lordship of Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire and approved his purchase of Hartford in March 1309.(6) It worked, at least in the short-term. Pembroke was after all barely in opposition and seen by all as a moderate. In April 1309, the extent of the bridge built between them became apparent, when Aymer agreed to join a commission that was sent to the pope at Avignon to bring about support for Gaveston’s return to England and the lifting of the sentence of excommunication which had been pronounced upon him by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Winchelsey should Piers return.

After Gaveston’s recall in 1309 from Ireland, the relationship between the two earls quickly began to deteriorate. As part of the political reform concessions promised by Edward for the return of Gaveston failed to materialise, Pembroke grew openly frustrated along with many others. Perhaps he felt betrayed, perhaps cajoled by those around him, but whatever the deciding factor was the earl briefly entered into a more clearly defined opposition. So much so that Edward was forced to issue a warning to Pembroke as well as Lancaster, Hereford and Warwick forbidding them to turn up at the next parliament armed.(7) Gaveston, affronted by the ongoing refusal of his peers to embrace him, took to calling his enemies nicknames and Pembroke was apparently awarded the title of ‘Joseph the Jew’, on account of his dark skin and hair colour.(8) This is the closest indication we have to any of Aymer’s characteristics, but given its nature, should be treated with caution.

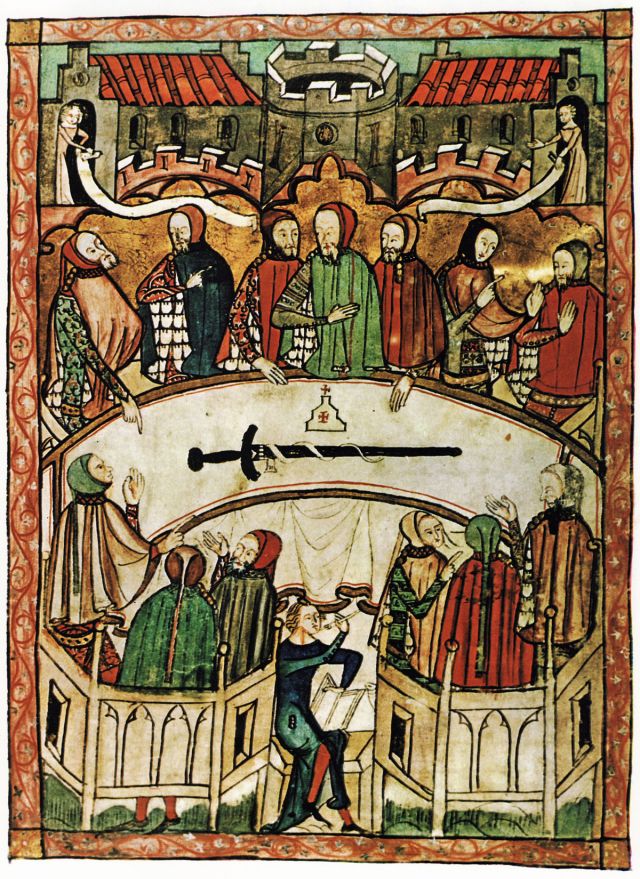

By 1310, opposition to Edward and Gaveston and the demand for political reforms grew so loud they could not be ignored. Forced to concede, the king granted under duress to a royal commission to conduct a review and recommend reforms for the good of the realm. Those appointed were to become known as Lord Ordainers and Pembroke was the first to be elected. His appointment, as the most moderate of those clamouring for reform was a carefully crafted statement sending out a signal to the king that he still had a chance of filling the commission with men who would not seek to undermine his royal authority. Unfortunately for Edward, hardline men such as Lancaster and Warwick would dominate the agenda. By the time the commission was ready to deliver its recommendations in late summer of 1311, the Ordinances as they were known, were a far reaching and revolutionary straight jacket designed to limit the power of monarchy far beyond that of Magna Carta. It was a direct attack on the king’s sovereignty. Worse still it demanded the third, and what was to be the final, exile of Gaveston which was duly forced from the king. Pembroke still tried hard to work with Edward during this highly charged political backdrop, but the king furious and not one to forget betrayal, pushed him away in anger.

So where did this leave Aymer? Temporarily out in the cold and no doubt nervous in his place of opposition. When Edward recalled Gaveston and overturned the Ordinances in early 1312, the nobles reacted violently. Pembroke and Surrey, both loyal servants of the crown, were chosen to arrest Gaveston then in the north with the king and bring him back south pending parliament. Eventually cornered at Scarborough castle, Gaveston temporarily sat out the siege which was conducted by Pembroke, Surrey and Henry Percy. Edward, at Knaresborough was frantic and wrote to Pembroke frequently suing for a temporary truce. Of all those likely to come to terms with his king, it was Aymer, a man of compromise and moderation. The settlement agreed between them was noble and fair, and if anything in favour of the king, an indication of Aymer’s natural loyalties. Gaveston was to be taken to Edward now at York, and there after discussion be removed south to his castle at Wallingford, where he was to await the next parliament which was summoned on 3 June to meet at Lincoln on 8 July.(9) If agreement could not be reached as to what would happen to Gaveston next by 1 August, Pembroke was to escort Piers back to Scarborough unhurt and the siege would continue. Should harm come to the earl of Cornwall during this exchange, then Pembroke, Surrey and Henry Percy’s lands would all be forfeit. Gaveston in turn made promises not to meddle or convince Edward to alter the terms of the agreement during the following months. The deal was struck.

Pembroke’s folly is to have assumed that his peers were as loyal or chivalrous as he. The agreement reached with the king at York had been one drawn up between Edward and his immediate opponents; opponents who were by all intents and purposes loyal to the crown. For those remaining hardline Lord Ordainers, the most extreme being the earls of Lancaster and Warwick, Pembroke’s treaty was anathema. As Aymer had not consulted with them they felt no inclination to uphold its terms. As Pembroke moved south with Piers, he left the earl of Cornwall at a manor at Deddington in Oxfordshire under a light armed guard whilst he wished to visit his wife Beatrice at his nearby manor of Bampton. On the following morning during Pembroke’s absence, Gaveston was forcibly seized by the earl of Warwick and thrown into Warwick castle to await a mock trial. During the nine days he was held captive there, Pembroke desperately sought Gaveston’s release. After all, should harm befall the earl of Cornwall then Pembroke’s lands and titles were forfeit.

At first he appealed to the king’s nephew the earl of Gloucester who promptly chided him and told him to take more care next time. Seeing no support forthcoming he appealed to the burgesses of Oxford for military aid but again no one was willing to help; the town too afraid to enter this dangerous affray. He grew desperate, and worse still was rendered unable to do anything to recover the situation. At dawn on the morning of 19 June, with Pembroke nowhere in sight, Piers Gaveston was led from Warwick castle by Lancaster, Hereford and others to Blacklow Hill, whilst the earl of Warwick lurked behind in his castle, and there he was handed over to two Welshmen and murdered; first being run through the stomach with a sword and then finally being beheaded.

Facing the edge of the precipice Pembroke did the only thing he could. He threw himself on Edward’s mercy. The king, despite his intense and immediate grief, welcomed Aymer back at his side. From this date onwards, Pembroke, disgusted at his treatment at the hands of his peers who had refused to honour his oath, remained loyal to the king. From June 1312 until the rise of Hugh Despenser the younger after 1317 and the Despenser War in Glamorgan in 1321, Pembroke held the principal position at court as key advisor to the king. Edward listened to and respected him during these intense years. What happened, and Pembroke’s eventual demise, is the subject of part two.

Stephen Spinks is author of ‘Edward II the Man: A Doomed Inheritance’, available for pre-order in hardback by clicking here at Waterstones Amazon and Amberley Publishing

Notes

(1) Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, 1307-24: Baronial Politics in the Reign of Edward II. J.R.S. Phillips. (Oxford University Press, 1972), 3.

(2) Ibid, 5.

(3) CFR, 1307-19, 6.

(4) Aymer, 24. CDS, 1272-1357, nos. 1214, 1280

(5) Ibid, 6.

(6) CPR, 1307-13, 145. Aymer, 29.

(7) CPR, 1307-13, 207

(8) Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall 1307-1312: Politics and Patronage in the reign of Edward II. J.S. Hamilton, 75.

(9) PW, II, i, 72. Vita, 24.

Facebook: Fourteenthcenturyfiend

Twitter: @SpinksStephen

6 thoughts on “A Lesson in Loyalty: The Life of Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke (Part One)”