Hugh Despenser the Younger had risen in both position and power since his marriage to Edward II’s niece, Eleanor de Clare, in 1306. Although the marriage arranged by Edward I was a great match and an acknowledgement of his father’s loyalty to the late king, it did not come with great tranches of land or any significant titles. For the most part of the next decade, the younger Despenser relied on income from his father’s extensive estates and through his wife’s dower, which frustrated his burning ambitions to achieve greater position and wealth. During the middle years of Edward II’s reign (r. 1307-1327), Hugh began to play a more direct role, present among the royal favourites but in the shadow of his father Hugh Despenser the Elder, who remained unswerving in his loyalty to Edward I’s son and heir. This loyalty allowed his own son to gain position at court and when the lands of the earldom of Gloucester were partitioned by the king in 1317 following the death of the late earl at Bannockburn in 1314, Despenser and his wife – one of the earl of Gloucester’s sisters – inherited the most important elements, which centred on the lordship of Glamorgan and included key castles like Caerphilly, Cardiff and many smaller manors. Despenser, overnight, had become a wealthy man. Other grants soon followed. In the autumn of 1320 he was made constable of Bristol Castle.[1] Only a year earlier, the magnates of England, including the leading noble of the day, Thomas Earl of Lancaster, who held back his characteristic hatred for the Despenser family, supported the younger Hugh’s promotion to the role of Chamberlain of Edward’s household, which was confirmed in the parliament of 1319. Suddenly, within the space of a handful of years, Despenser was moving in the highest of circles.

The warning signs, with the benefit of hindsight, had been there from the start. His hotheaded action in physically attacking a relative by marriage, John Roos, in Lincoln Cathedral in the very presence of the king in 1316 over a simple dispute was both unbecoming and also an infringement of the court rules. The resulting fine, which Despenser never paid, demonstrated both his attitude and overweening pride. He had a violent temper and was unafraid to express it in order to achieve this aims. What both the king and the magnates of England had not appreciated, however, was this behaviour was typical rather than extraordinary, and unwittingly they had invited a wolf in among the fold; and this wolf in particular was calculating, highly manipulative, dangerous to those around him and to Edward in particular.

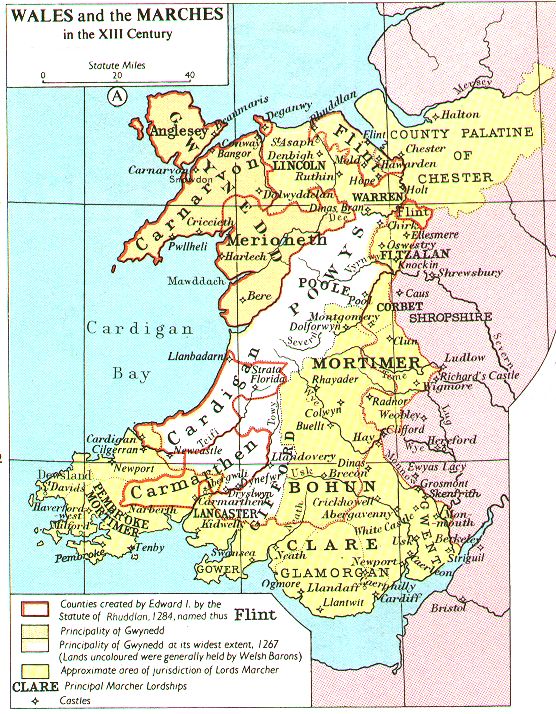

Despenser the Younger did not rest after his wife inherited part of her late brother’s estates. He soon devised a plan to acquire lands adjacent to his lordship of Glamorgan in South Wales to consolidate his power and all but set himself up as a new Earl of Gloucester. His modus operandi rested on coercion, bribery and open violence. He soon singled out the king’s favourite, Hugh Audley the Younger, who was the husband of Margaret, sister to Hugh’s wife’s Eleanor, Margaret herself the former widow of the king’s murdered lover, Piers Gaveston. The area of Gwynllwg, which sat in south Glamorgan and valued at £458, was a prize possession and Despenser wanted it. Before Audley had the opportunity to secure the homages of his inherited tenants, Despenser raced to Gwynllwg and received the homages himself, effectively forcing Audley off the land. Audley turned to King Edward for help, who commanded Despenser to hand the land over to his favourite, but Despenser prevaricated and the king failed to pursue the matter with any sense of urgency. Under pressure, Hugh Despenser turned to rough diplomacy to seal the deal. Audley and Margaret eventually, and somewhat reluctantly, agreed to hand over Gwynllwg in return for six manors in England, the bargain very much in Despenser’s favour.[2] Other lands quickly fell under his control as he extended his hold to the west of Glamorgan when Edward granted him the Cantref Mawr and other lands. When the Dowager Countess of Gloucester died on 2 July 1320, he also inherited the town of Tewkesbury and more, while all the time setting his sights on castles associated with the lordship of Brecon, which had been given to Roger Mortimer of Wigmore in 1316.[3] His ambition was self-evident; his tactics dangerous.

The Marcher lords, who were magnates with lands along the Welsh border and in South Wales, held a greater degree of autonomy and power in this area than magnates elsewhere in England, a hangover from the time of the Norman Conquest and the centuries that followed when subduing the Welsh was a priority delegated by the monarch to robust and aggressive lords who relished the opportunity to advance their own personal wealth and status. After Edward I’s conquest of Wales at the time of Edward II’s birth in April 1284, the original role of the Marcher lord became less important, if not moribund, but nevertheless their independent authority remained potent. As Despenser began a calculated campaign to build up both land and titles in South Wales, he too amassed significant independent powers in the region by virtue of his acquisitions, which began to rival and threaten the established Marcher lords who, for generations, had nursed their own ambitions. The Marches were ruled by a strict code, by close family ties and age-old customs. Despenser was an outsider and viewed with suspicion.

By 1320, Hugh Despenser the Younger, still not content with his lot, turned to the lordship of Gower, owned by William de Broase who, with no male heir, had settled the lordship on his daughter’s son, John de Mowbray. However, the avaricious William subsequently spent years undermining his own settlement, offering the reversion of his estates to anyone who would pay the highest fee. The fee kept changing. With serious interest shown by the Earl of Hereford and Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, negotiations had been underway for years. In the autumn of 1319 Hugh Despenser entered the race, opening talks with de Broase and either offered the highest price to date, or applied other forms of bargaining, and soon looked to be on the winning pledge. Securing Gower, with its administrative centre based at Swansea, would make Despenser uncomfortably powerful in the region. For the Marcher lords, it was one acquisition too many.

Nerves began to fray and before long the Marcher lords, including Roger Damory – Edward II’s waining favourite at this time – Roger Clifford and John Gifford, felt the need to band together to counter the threat imposed by Despenser. In a moment of pique, John de Mowbray took the initiative and seized the lordship before his unscrupulous father-in-law could give away his wife’s inheritance. Despenser, unaccustomed to failure, was furious and turned to Edward claiming that Mowbray had entered the lordship without the king’s royal licence (something Despenser therefore himself had done with the Gwynllwg lands, if his argument was to be treated evidentially). It mattered little either way for the Marcher lords reminded the king that in the March his licence was not required, following ancient law and custom, but under Despenser’s growing personal and intimate influence over the king, Edward decided otherwise. On 26 October 1320, at the Westminster parliament following his return from France, Edward ordered that the lordship of Gower be taken into royal hands.[4] For now, the king would hold it – and determine who should possess it in the future. The king’s decision was highly unusual and royal officials led by Richard Foxcote were fiercely resisted by the inhabitants of Gower who remained loyal to Mowbray.[5] Under the threat of local aggression, Edward began to waver in his conviction and was prepared to grant the lordship to Mowbray after all but, under Despenser’s influence, changed his mind at the last minute.[6] As chamberlain, Hugh had the benefit of being always in Edward’s presence and was therefore best placed to control the situation, influencing the only man who could settle the issue. Edward’s brother-in-law and long serving councillor the Earl of Hereford, with Mowbray in tow, pleaded with the king to reconsider, but Edward refused their petition, removing at a stroke any further legal recourse. Despenser was pullings the strings and began threatening those about him. He openly spoke to treachery against the king and was overheard saying that he would avenge the death of his grandfather – another Hugh Despenser, formerly Justiciar of England – who was killed at the battle of Evesham by the Mortimers in 1265.[7] Beyond his land grab, Despenser clearly had some old axes to grind.

The material outcomes of Despenser’s strategy was ultimately wealth and status, but he could not achieve either in their entirety without political power to hold onto his ill-gotten gains, and in medieval England, only one man could give him that. Despenser who was also in character possessive and domineering, put these skills to best use. By the end of 1320 he had become so confident of his hold over Edward – the two of them most likely lovers by this point – that Despenser was able to demonstrate his control during public audiences. The contemporary chronicler Murimuth notes, ‘if the magnates were allowed to talk to the king, Despenser would listen to the conversation and reply freely on his [Edward’s] account’.[8] While it was customary for the king to speak through another while in public or at council, Murimuth implies that Despenser did not wait to find out the king’s will, but rather made the decisions himself and answered for the king. If this were true and widespread, Despenser was exercising the royal prerogative as though he was king himself. In a letter to John Inge, his sheriff of Glamorgan, he remarked ‘that the times changed from one day to another; envy was growing against him, and especially among the magnates, because the king treated him better than any other’. He went on to order Inge to watch his affairs so that ‘we may be rich and may attain our ends’.[9] Despenser was proving to be ruthless in pursuit of his personal ambition and if controlling the king was the only way to secure it, he was both calculating and rapacious enough to bring it about.

With this in mind, it was clear that Hugh Despenser was now engineering a permanent settlement of Gower in his favour and after that, the Marcher lords could not be sure if their lands were next.[10] Edward had removed their legal recourse through his order over Gower, leaving open rebellion as their only option, and in the minds of the Marcher lords, responsibility lay firmly on one man. Despenser needed to be separated from the king before they were all consumed.

See part two for what happens next…

Stephen Spinks is author of a medieval series of works focussing on the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. His books, available globally, include; Edward II the Man: A Doomed Inheritance and Robert the Bruce: Champion of a Nation

Notes

The content and words for this article are drawn extensively from material outlined in chapter 18 of Spinks, Stephen. Edward II the Man: A Doomed Inheritance (Stroud, 2017), 158-168.

Further reading:

All the King’s Men: The Forgotten Royal Favourites (Part Two) [18 March 2017, fourteenthcenturyfiend.com] (click here)

All the King’s Men: The Forgotten Royal Favourites (Part One) [3 January 2017, fourteenthcenturyfiend.com] (click here)

Extended evidential footnotes:

[1] CPR, 1317-21. 514.

[2] CPR, 1317-21, 60, 103, 415, 456.

[3] Pugh, T.B. ‘Marcher Lords of Glamorgan and Morgannwg, 1317-1485’ in Glamorgan County History, III: The Middle Ages (1971), 168. Phillips, Seymour, Edward II (New Haven & London, 2010), 365.

[4] CCR, 1318-23, 268

[5] CPR, 1317-21, 547. CFR, 1319-27, 41, 43.

[6] Annales Paulini 1307-1340 in W. Stubbs, ed Chronicles of the Reigns of Edward I and Edward II, Vol I, Rolls Series, lxxvi (London, 1882), 237. Davies, J.C ‘The Despenser War in Glamorgan’ in TRHS, 3rd series, ix (1915), 36-42.

[7] Vita Edwardi Secundi, ed N. Denholm-Young (London, 1957), 108-9.

[8] Adae Murimuth Continuation Chronicarum, ed E.M. Thompson (London, 1889), 33.

[9] Phillips, 367. Goronwy, J. Edwards, Calendar of Ancient Correspondence, 219-20.

[10] Anonimalle Chronicle 1307 to 1334 from Brotherton Collection MS 29, ed. W.R. Childs and J. Taylor (Yorkshire Archaeological Society, cxxxi, part I (London, 1906), 92. Phillips, 368.

One thought on “Ancient Customs & Conflict: Edward II & the Contrariant Rebels (Part One)”